It was a frightening realization of my early 30s that had I not moved away from my family and my hometown when I did, I would already have been dead. I have no doubt that I would have committed suicide by the time I was 25, I felt so alone and ashamed and afraid of my desires. LGBT youth are five times more likely to have attempted suicide than straight youth. Luckily, I escaped my prison in time to discover a life.

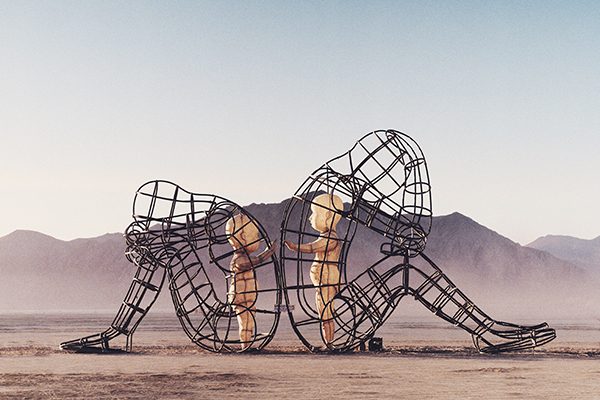

For many of us in one (or more) of life’s many closets, the existential loneliness is what prompts thoughts of suicide: If I am already this alone in the universe, feeling this much pain and alienation, why not just end it? Carl Jung says there are only two cures for existential loneliness: love and spirituality. All other attempts to soothe our human angst are shortcuts to these, substitutes for them, pale imitations by virtue of being chemical or sensory experiences, or particular behaviors and beliefs that we tell ourselves will “ward off the evil spirits.”

For most people, love is the easiest and most pleasant way to stave off existential loneliness, usually love of one’s partner and family. The fact that this model works for the vast majority of people does NOT mean that it works for everyone. In fact, its predominance in the culture produces heteronormativity and couple-normativity, what most people think will make “everyone” happy. But the pressure—the brainwashing, even—from society to be straight and to be coupled can suffocate or paralyze those who are not 100 percent heterosexual or who do not thrive as part of a monogamous couple. Where is the human comfort for these people?

The drive for love, for sex, for intimacy, for physical closeness with another human being, these do not necessarily have to be fulfilled by one romantic, monogamous partner. Evolutionary forces (bolstered by religion) have promoted the opposite of this, however, to the point of even outlawing and punishing other choices. Now, in 2018, open relationships, polyamory, and alternative lifestyles are increasingly presenting themselves as options to clients of mine, as are same time, next year/month/week relationships, and even deep friendships that include cuddling but not sex—or vice versa. The sex drive can be satisfied in many different ways, as can the drive to be connected to others.

In therapy we try to find out what are truly our wants and needs for connection with others, as opposed to those we have been force-fed by family, friends, and society. For many of us, however, it can be very hard to accept that our path in this matter is not that of others. Admitting who we are and what we need (and don’t need or want) is the first step in living life honestly and joyfully—the only way to coexist with existential loneliness.

David Bowman LMFT is a licensed psychotherapist based in Los Angeles, California.

Photo credit: Gerome Viavant UNSPLASH

Tags:

Tags: